Exploring Protein's Role in Satiety and Energy Balance

Educational content only. No promises of outcomes.

Protein Digestion Basics

When protein is consumed, it undergoes a series of biochemical processes beginning in the stomach and continuing through the small intestine. Proteolytic enzymes—primarily pepsin in the stomach and trypsin in the small intestine—break down protein molecules into progressively smaller units: polypeptides, then amino acids and dipeptides.

This process, called proteolysis, is more metabolically costly than the digestion of carbohydrates or fats. The body expends energy to produce and maintain these enzymes, regulate stomach acid, and power the mechanical and chemical breakdown process. This fundamental mechanism forms the foundation for understanding how dietary protein influences broader physiological responses.

Key Satiety Hormones Released

Protein consumption triggers the release of several hormones central to the perception of fullness:

GLP-1 (Glucagon-Like Peptide-1)

Released from intestinal L-cells in response to nutrient presence. GLP-1 acts on the brain's appetite centres and slows gastric emptying, extending the sensation of fullness.

CCK (Cholecystokinin)

Released from the duodenum and jejunum following protein and fat intake. CCK sends satiety signals to the brain and regulates stomach contraction and pancreatic enzyme secretion.

PYY (Peptide YY)

Released from distal intestinal cells, PYY travels to the brain where it reduces hunger signalling and appetite. Protein strongly stimulates PYY secretion.

Comparison of Macronutrient Satiety Effects

Protein

Strongest satiety signal

High thermic effect, sustained hormone release, slower gastric emptying.

Carbohydrates

Moderate satiety signal

Moderate thermic effect, brief hormone response, variable satiety depending on type and fibre.

Fats

Variable satiety signal

Lower thermic effect, delayed but prolonged hormone release, high energy density.

Thermic Effect of Protein

The thermic effect of food (TEF), also called diet-induced thermogenesis, represents the energy cost of digesting, absorbing and processing nutrients. Protein requires significantly more energy to process than carbohydrates or fats.

Approximately 20-30% of protein calories are expended during digestion and metabolism, compared to 5-10% for carbohydrates and 0-3% for fats. This higher metabolic cost reflects the complexity of proteolytic pathways and amino acid metabolism. The body's elevated energy expenditure during protein digestion contributes to the feeling of fullness beyond simple volume or caloric intake.

Gastric Emptying Influence

Gastric emptying—the rate at which the stomach releases its contents into the small intestine—is a critical regulator of appetite and satiety signals. Protein slows gastric emptying significantly compared to other macronutrients, meaning protein-containing meals remain in the stomach longer.

This delayed gastric clearance is mediated partly through CCK release and partly through direct stimulation of gastric mechanoreceptors. The prolonged stomach distention and the extended period during which digestive hormones are secreted both contribute to sustained fullness signalling to the brain.

Neural Pathways in Fullness Perception

Signals of fullness reach the brain through multiple channels. The vagus nerve carries mechanical and chemical signals from the stomach and intestine directly to the hypothalamus and other appetite centres. Hormones like GLP-1, CCK, and PYY circulate in the bloodstream and directly activate receptors in brain regions controlling hunger and satiety.

Additionally, nutrient-sensing mechanisms in the gut initiate neural reflexes that affect appetite centres before food even reaches the intestine. The integration of these mechanical, hormonal, and neural signals creates the complex sensation of fullness. Individual variations in neural sensitivity and receptor expression influence how pronounced satiety signals feel across different people consuming identical meals.

Individual Response Variability

While the basic physiological mechanisms of protein-induced satiety are well-established, responses vary significantly between individuals. Genetic differences in hormone receptor sensitivity, variations in enzyme expression, and differences in neural pathway development all influence satiety perception.

Factors including prior dietary exposure, metabolic state, stress levels, sleep quality, and even gut microbiota composition can modulate satiety hormone release and brain sensitivity to those signals. Research demonstrates substantial inter-individual variability in subjective fullness ratings following identical protein doses, underscoring that satiety is a complex, individualised phenomenon shaped by both biology and lived experience.

Common Dietary Protein Sources

Protein exists across diverse food categories, each with unique amino acid profiles and nutritional contexts:

- Fish (salmon, cod, tuna): Complete protein with all essential amino acids; rich in omega-3 polyunsaturated fats.

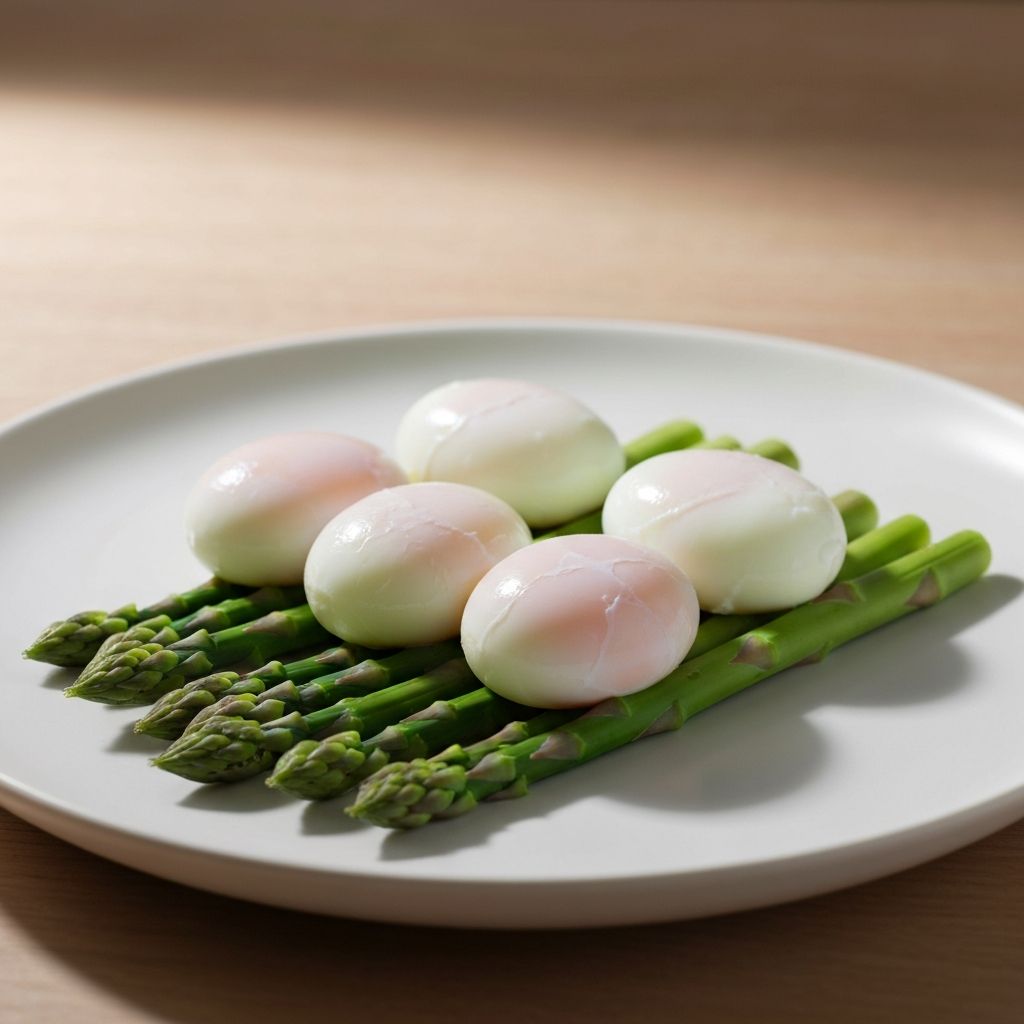

- Eggs: Complete protein containing all nine essential amino acids; whole eggs include choline and lutein.

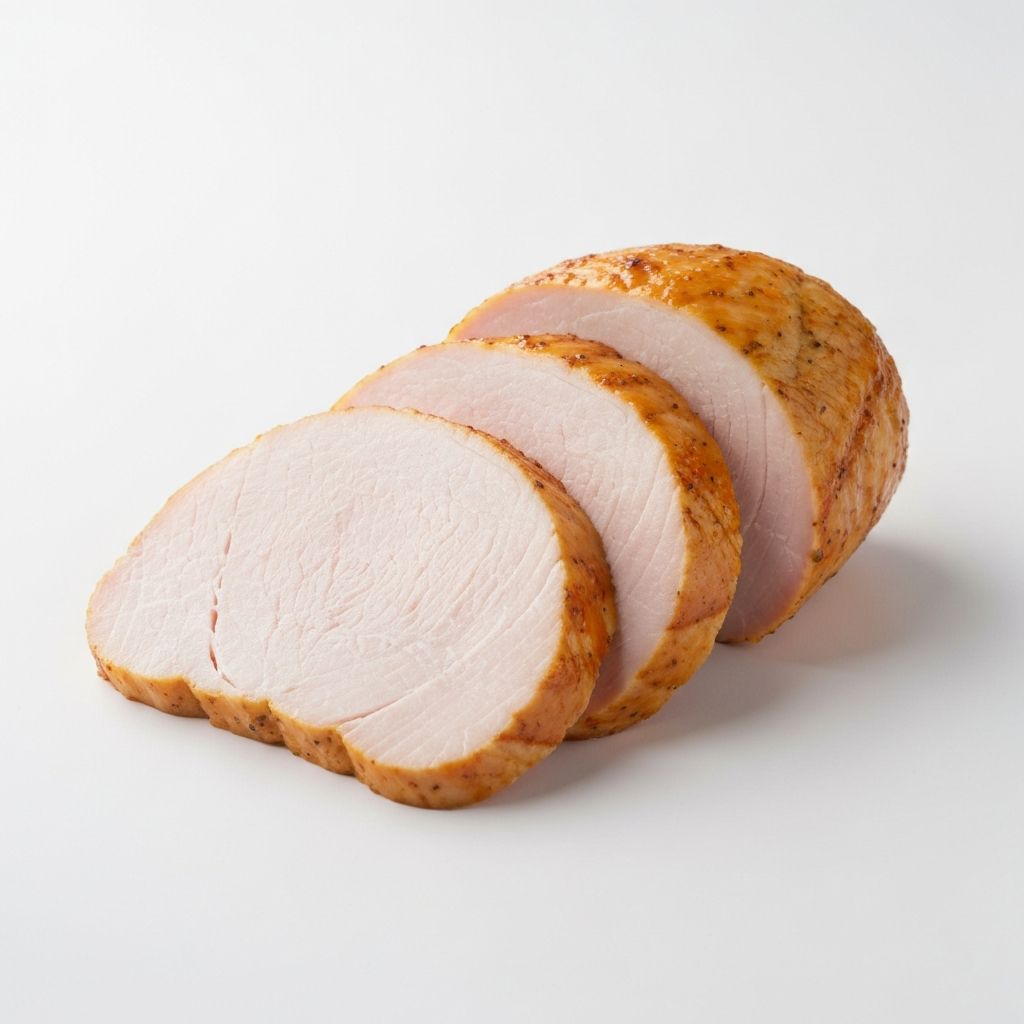

- Poultry (chicken, turkey): Lean protein sources with high amino acid density relative to fat content.

- Legumes (lentils, beans, chickpeas): Plant-based proteins with fibre and polyphenols; lower in certain essential amino acids but rich in others.

- Dairy (Greek yoghurt, cottage cheese): Complete proteins; dairy sources provide calcium and contain lactose.

- Nuts and seeds: Plant-based protein with healthy fats, minerals, and fibre.

- Grains (quinoa, ancient grains): Incomplete proteins but contribute meaningfully when combined with other sources.

Explore Detailed Mechanisms

How Protein Influences Key Satiety Hormones

Deep dive into GLP-1, CCK, and PYY mechanisms and their roles in satiety signalling.

Explore this mechanism →

The Thermic Effect of Food: Protein's Higher Cost

Understanding why protein digestion requires more energy than other macronutrients.

Explore this mechanism →

Gastric Emptying and Protein's Role

How protein slows stomach-to-intestine transit and extends satiety signalling.

Explore this mechanism →

Neural Mechanisms of Protein-Induced Fullness

Brain pathways, vagal signalling, and neural integration of satiety information.

Explore this mechanism →

Variability in Satiety Responses to Protein

Why individuals respond differently to protein and what influences this variation.

Explore this mechanism →

Amino Acid Profiles Across Common Protein Sources

Nutritional composition and amino acid profiles of diverse dietary proteins.

Explore this mechanism →Frequently Asked Questions

No. Protein does not directly cause weight loss. This exploration examines how protein influences satiety signals and digestion mechanisms. Individual outcomes depend on many factors including overall energy balance, activity level, genetics, and lifestyle. No outcome should be assumed from protein consumption alone.

Multiple mechanisms converge: protein has a higher thermic effect (requiring more energy to digest), it slows gastric emptying, and it stimulates stronger release of multiple satiety hormones including GLP-1, CCK, and PYY. The combination of these factors creates a more pronounced fullness signal compared to other macronutrients.

CCK acts rapidly (within minutes) and affects both the stomach and brain to signal fullness. GLP-1 slows stomach emptying and acts on appetite centres. PYY is released from lower intestinal cells and works over a longer timeframe. Together, they create overlapping, sustained satiety signalling.

The thermic effect of food (TEF) is the energy your body expends to digest, absorb, and process nutrients. Protein requires 20-30% of its calories for TEF, compared to 5-10% for carbohydrates and 0-3% for fats. This higher cost reflects complex enzymatic and metabolic pathways involved in protein processing.

No. Individual factors—including genetic variation in hormone receptors, stomach muscle composition, and prior dietary patterns—influence how much protein slows gastric emptying. Research shows considerable variability in gastric transit times across individuals consuming identical protein amounts.

Yes. Neural sensitivity to hormonal signals depends on receptor expression, developmental factors, metabolic state, and environmental influences. Some individuals may experience more pronounced fullness signals from the same hormone concentration due to variations in brain receptor density or signalling efficiency.

Research suggests there may be small differences in satiety hormone responses to different protein sources due to amino acid composition and digestion rate, but the overall effect is that most dietary proteins trigger these mechanisms. The magnitude varies individually.

Timing influences the rate at which satiety hormones are released but does not fundamentally change the mechanisms. Protein consumed at any point triggers the same physiological pathways, though the timeline and intensity of the response may vary.

The vagus nerve carries signals from the gut directly to the brain, transmitting information about stomach distention, nutrient presence, and hormone levels. These neural signals integrate with hormonal messages to create the conscious sensation of fullness.

Yes. Genetic variation in appetite hormone receptors, digestive enzyme expression, and neural signalling genes can influence how strongly an individual experiences satiety signals from protein. This contributes to the substantial inter-individual variability observed in research.

The gut microbiota influences digestion rates, the production of short-chain fatty acids, and the regulation of intestinal hormone release. Changes in microbiota composition can modulate satiety hormone levels, contributing to individual differences in fullness perception.

No. This content is educational and explains physiological mechanisms. It is not medical advice, nutritional guidance, or a substitute for consultation with qualified healthcare professionals regarding individual dietary choices or health concerns.

Continue Exploring

Discover more about the physiological mechanisms underlying nutrition and energy regulation.

Explore our research summaries Learn about KinvaraLimitation and Context

Educational content only. The materials presented on Kinvara are informational in nature and do not constitute medical advice, dietary recommendations, or clinical guidance. The physiological mechanisms described are based on scientific literature and represent current understanding of these processes.

No individual prediction. These mechanisms are described in general terms. Individual responses to dietary protein vary significantly based on genetics, health status, lifestyle factors, and many other variables. No specific outcome should be anticipated from protein consumption.

Not a substitute for professional guidance. Individuals with specific health concerns or dietary questions should consult qualified healthcare professionals, registered dietitian-nutritionists, or medical practitioners who can assess individual circumstances.